|

| Mechanism of RNA interference (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| One molecule of the Dicer-homolog protein from Giardia intestinalis, colored by domain (PAZ domain yellow, platform domain red, connector helix blue, RNase and bridge domains green). Dicer is an RNase that cleaves long double-stranded RNA molecules into short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) as a first step in the RNA interference response, and also initiates the formation of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

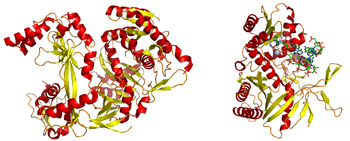

| Left: (Image:1u04-argonaute.png) A full-length argonaute protein from the archaea species Pyrococcus furiosus. Right: (Right:Image:1ytu_argonaute_dsrna.png) The PIWI domain of an argonaute protein in complex with double-stranded RNA. The base-stacking interaction between the 5' base on the guide strand and a conserved tyrosine residue (light blue) is highlighted; the stabilizing divalent cation (magnesium) is shown as a gray sphere. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Scientists and Biotechnology companies are developing what could become the next powerful weapon in the war on pests – one that harnesses a Nobel Prize-winning discovery to kill insects and pathogens by disabling their genes.

By zeroing in on a genetic sequence unique to one species, the technique has the potential to kill a pest without harming beneficial insects. That would be big advance over chemical pesticides.

“If you use a neuro-poison, it kills everything,” said Subba Reddy Palli, an entomologist at the University of Kentucky who is researching the technology, which is called RNA interference, or RNAi. “But this one is very target-specific.”

But some specialists fear that releasing gene-silencing agents into fields could harm beneficial insects, especially among organisms that have a common genetic makeup, and possibly even human health.

“To attempt to use this technology at this current stage of understanding would be more naïve than our use of DDT in the 1950s,” the National Honey Bee Advisory Board said in comments submitted to the United States’ Environmental Protection Agency, which regulates pesticides.

The approach is of interest to bee keepers because one possible use, under development by Monsanto, is to kill a mite that is believed to be at least partly responsible for the mass die-offs of honeybees in recent years.

Monsanto also has applied for regulatory approval of corn that is genetically engineered to use RNAi to kill the western corn rootworm, one of the costliest of agricultural pests. The company is also trying to develop a spray that would restore the ability of its Roundup herbicide to kill weeds that have grown impervious to it.

Some bee specialists said they would welcome attempts to use RNAi to save honeybees. Groups representing corn, soybean and cotton farmers also support the technology.

For a decade, corn growers have been combating the rootworm by planting so-called BT crops that are genetically engineered to produce a toxin that kills the insects when they eat the crop. But rootworms are now evolving resistance.

RNA interference is a natural phenomenon that is set off by double-stranded RNA. DNA, which is what genes are made of, is usually double stranded, the famous double helix. But RNA, which is a messenger in cells, usually consists of a single strand of chemical units representing the letters of the genetic code. When a cell senses a double-stranded RNA, it acts as if it has encountered a virus. It activates a mechanism that silences any gene with a sequence corresponding to that in the double-stranded RNA.

Scientists quickly learned that they could deactivate virtually any gene by synthesizing a snippet of double-stranded RNA with a matching sequence.

The scientists who first unraveled this mechanism won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and it was initially assumed that most of the use would be in medicine – for example, drugs that could turn off essential genes in pathogens or tumors.

So far, researchers have found it difficult to deliver the RNA through a person’s bloodstream into the cells in the body where it is needed.

But beetles like the corn rootworm can simply eat the double-stranded RNA to set off the effect. One way to get insects to do that is to genetically engineer crops to produce double-stranded RNA corresponding to an essential gene of the pest.

Monsanto’s rootworm-killing corn is one of the first in which the crop has been engineered specifically to produce a double-stranded RNA.

Monsanto is also looking at putting RNA into sugar water fed to honeybees to protect them from the varroa mite. The way to fight the mite now is to spray pesticides that can also harm bees.

“We were trying to kill a little bug on a big bug,” said Jerry Hayes, the head of bee health at Monsanto.

If the RNAi is directed at a genetic sequence unique to the mite, the bees would not be harmed.

Some scientists are calling for caution, however. In a paper published last year, two entomologists at the United States’ Department of Agriculture warned that because genes are common to various organisms, RNAi pesticide might hurt unintended insects.

One study at the University of Kentucky and the University of Nebraska found that a double-stranded RNA intended to silence a rootworm gene also affected a gene in the ladybug, killing that beneficial insect.

In a paper prepared for a meeting earlier this year, E.P.A. scientists said RNAi represented “unique challenges for ecological risk assessment that have not yet been encountered in assessments for traditional chemical pesticide.”

Taken from TODAY Saturday Edition, March 22, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment