|

| larger animation (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

| The supermassive black holes are all that remains of galaxies once all protons decay, but even these giants are not immortal. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

|

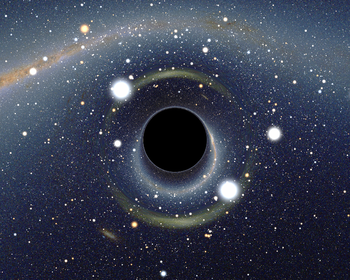

| Simulated view of a black hole in front of the Large Magellanic Cloud. The ratio between the black hole Schwarzschild radius and the observer distance to it is 1:9. Of note is the gravitational lensing effect known as an Einstein ring, which produces a set of two fairly bright and large but highly distorted images of the Cloud as compared to its actual angular size. (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Black holes, the ultradense objects predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, have extraordinary gravity: Everything is sucked in, even light, and virtually nothing leaks out.

Now, for the first time, astronomers may have a chance to watch as a gas cloud that has been hurtling toward the center of the Milky Way collides with a black hole that lies just 26,000 light-years from Earth. (While scientists expect to observe the event beginning in March or April, it occurred 26,000 years ago.) The gas cloud is as massive as three Earths – but no match for the black hole, Sagittarius A**, which has the mass of four million suns.

“This is a rare opportunity to witness spoon-feeding of a black hole,” said Avi Loeb, a theoretical astro physicist at Harvard. “Will the gas reach the black hole, and if so, how quickly? Will the black hole throw up or spit the gas out in the form of an outflow or a jet?

If the black hole devours a sizable chunk of the cloud, a digestive process that could take many months to years, fireworks could ensue. Heated to billions of degrees as it spirals inward, the doomed gas cloud may emit a last gasp of radiation, ranging from radio waves to X-rays.

“We will learn something, no matter what happens,” said Andrea Ghez, an astronomer at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has monitored the galactic center since 1995. Black holes are believed to be at the center of nearly every large galaxy.

The action is likely to unfold in two acts, said Stefan Gillessen of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany.

His team discovered the gas cloud, G2, in 2011.

After the cloud, already stretched into a spaghetti-like strand by the black hole’s gravity, makes its closest approach to Sagittarius A*, its distance from the black hole will be about 200 times Earth’s distance from the sun. Nonetheless, the passage of G2 near Sagittarius A* might be near enough to plow into the outer edge of the swirling disk of matter believed to surround the black hole.

The shock wave generated by that encounter might create X-rays and radio waves that could be detected by telescopes.

If the cloud contains a star at its center, as some astronomers have proposed, it may generate more light, said Sera Markoff of the University of Amsterdam.

The encounter could have another effect: Disruptions in the cloud might alter the direction in which radio waves vibrate as they travel through. Simultaneous observations with telescopes tuned to different radio wavelengths might discern the waves’ twists, giving astronomers new details about the cloud’s properties, said Geoffrey Bower, a radio astronomer with the Taiwanese organization Asiaa, in Hilo, Hawaii.

But most of the potential fireworks are at least a year away, perhaps decades. That is how long it may take material torn from G2 to spiral inward through the black hole’s feeding disk, coming 100 times closer to the hole than it is now. At that location, gas becomes hot enough to radiate before it is swallowed.

Next year, the Event Horizon Telescope, an array of radio telescope, will gain enough acuity to discern the light that just misses being dragged into Sagittarius A*, but is bent into a halo. (That level of acuity could make out an orange on the surface of the moon, said the project’s leader, Sheperd Doeleman, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Haystack Observatory.) Deviations from the predicted shape of the halo would indicate Einstein’s theory of gravity needs revision.

For now, Professor Loeb said, astronomers are looking forward to the encounter. “The experience is as exciting for astronomers as it is for parents taking the first photos of their infant eating.”

Taken from TODAY Saturday Edition, March 8, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment